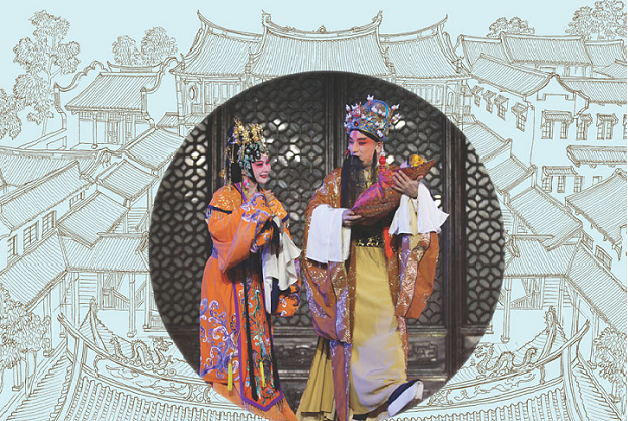

The Kunju Opera Grievance from a Former Birth was written, in collaboration with the Zhejiang Kunju Opera Troupe, at the Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong in order to pass on and develop Chinese culture. The opera is one of several composed on the basis of Buddhist sutras and parallel prose narrative texts. In 2012, the Chinese Zhejiang Kunju Opera Troupe performed the opera in the Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong with utmost artistry, deeply impressing the Hong Kong audience – the performance was a great success, winning praises and accolades and very positive reviews. We are deeply grateful to Ven. Wang Fun for granting us unconditional rights to perform the original opera in the Virtue Hall of the Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery.

The Kunju Opera Grievance from a Former Birth was written, in collaboration with the Zhejiang Kunju Opera Troupe, at the Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong in order to pass on and develop Chinese culture. The opera is one of several composed on the basis of Buddhist sutras and parallel prose narrative texts. In 2012, the Chinese Zhejiang Kunju Opera Troupe performed the opera in the Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong with utmost artistry, deeply impressing the Hong Kong audience – the performance was a great success, winning praises and accolades and very positive reviews. We are deeply grateful to Ven. Wang Fun for granting us unconditional rights to perform the original opera in the Virtue Hall of the Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery.

Kunju Opera is one of the oldest Chinese traditional operatic performance genres. It has long ago completely immersed itself within Chinese culture, which it has also influenced and developed. The oldest Buddhist sutras, such as the Vimilakīrti Sutra, the Sutra of the Meditation on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life and the Ajātaśāstru Sutra, have all transmitted moral teachings to society based on the abhorrence of evil and the exhortation to do good. These scintillating texts have deeply moved many readers. At the same time that they create artistic beauty they even more effectively spread the vision of the Dharma and the enchanting power encapsulated in the verse:

“bluegreen bamboo, yellow flowers: all subtle meanings; the bright moon in the clear stream illumines the heart of Zen.”

For over a thousand years, Buddhist sutras and parallel prose narratives have provided stories for operas, which actors and artist have performed in a hundred different resplendent ways. Grievance from a Former Birth draws from and rewrites passages from the Vimilakīrti Sutra, the Sutra of the Meditation on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life, the Ajātaśāstru Sutra and the Maha-Parinirvana Sutra.

The opera tells the story of King Bimbisāra of the ancient Indian kingdom of Magadha, who lived in the city of Rajagr̥ha. In his middle years he still had no son, and he feared that there would be no successor to the throne. A soothsayer forecasted that in a mountain nearby there was a hermit who would die in three years time, and who would be reincarnated as a Prince. King Bimbisāra fervently prayed for a son, and ordered that the hermit should be hurried to his death. The hermit grew angry and died quickly, and he was reborn full of anger and resentment in the King’s palace. When the Royal Consort Vaidehi gave birth to the child Prince Ajātaśātru she was delighted to have a son, but did not realize that she had planted the seeds of resentment within the family.

After the prince grew up, he rebelled against his parents. He took the bad counsel of the evil advisor Devadatta. He fomented a coup in the palace, and seized the throne, crowning himself as King. He imprisoned his parents in the dungeon, and refused them food or water, desiring that they starve to death. Reduced to this extremity, King Bimbisāra and his royal consort wept bitterly in their prison cell, and begged the Buddha to save them. This moved the Buddha to send forth his radiance and speak the Dharma.

The Buddha’s words formed the Sutra of the Meditation on the Buddha of Immeasurable Life, which was the first sutra to describe the Dharma gateway to the Western Paradise of the Pure Land. The sutra also taught the three karmic deeds: to be filial and merciful, to cultivate the ten good deeds, and to recite Mahayana sutras. The Buddha used his supernatural powers to enable the Royal Consort Vaidehi to personally see the Three Saints of the West and the Western Paradise. The Buddha taught her to make a vow to be reborn in the Pure Land, and initiated her as to how to practice the sixteen methods of meditation and observation. Prince Ajātaśāstru, after the death of his father and mother, proclaimed himself King. His evil deeds manifested themselves karmically, and his body was racked with pain and disease. He realized that this was the karmic result of his rebellious and false ways. The Buddha compassionately spoke the Dharma to him, causing his illness to vanish and his sins to be forgiven, plucking out the root of his bad actions. He relinquished his hatred, untied his resentments and resolved his entanglements.

The opera transmits both moral teachings and artistic functions, symbolically depicting the good and evil within human nature, revealing how hatred and resentments are the root causes of wrong actions, and showing that only through sincere repentance can one obtain purification and release.

The Zhejiang Kunju Opera Troupe has accumulated many years of assiduous development of their performance skills. They search for refinement on top of refinement. This public performance will undoubtedly be enlightening for the Singapore audience, fusing the spirit and the heart through a feast of the arts.

Translated by Professor Kenneth DEAN Head of Department of Chinese Studies National University of Singapore