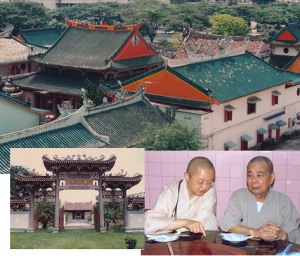

In 1987, many areas of the monastery constructed in wood were found to be heavily infested with termites. The structures of the halls were also in a precarious position since they were on the verge of decaying. A report from the Institute of Engineers in 1989 indicated that the monastery structure faced the possibility of a collapse. In 1990, Venerable Wang Fun, temple superintendent of Chi Lin Nunnery in Hong Kong, was invited by Shuang Lin Monastery to promote the Dharma, as well as to give a lecture on the subject of Buddhist monastery. The venerable observed that Shuang Lin Monastery had a complete layout with an exquisite Minnan construction style that was visible on the Mahavira hall as well as the Hall of the Celestial Kings. He was pleasantly surprised at being able to see such work existing outside of China while at the same time lavishing praise on it. Yet he recognized the need to restore both halls based on their original style, given that they have not been maintained for a long time. This would allow the preservation of the historical and artistic value of key cultural relics, a planned reconstruction of other halls in a complementary manner, and the opportunity to build upon the essence of the Chinese Buddhist architecture. The venerable permitted full support and assistance towards the planning of the reconstruction.

24th of May 1991, Shuang Lin was approved by the Registry of Societies as a societal group, with its official name being registered as Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery. At the smae time the management committee of Shuang Lin Moanstery was formed. The venerable permitted full support and assistance towards the planning of the reco with abbot Master Tham Sean as the first chairperson of the committee. The restoration committee was overseen by temple superintendent Venerable Wai Yim, with Venerable Wang Fun as the consultant for Buddhist artistry. In addition, the commitee sought the opinions of various construction experts from China. These included Mr Xue Xing Jian from the Construction Comprehension Reconnaissance Research Design Institute who oversaw the surveying and mapping work, and Messrs Li Zhu Jun and Song Sen Cai from the Beijing Municipal bureau of Cultural Heritage, who were in charge of providing a resotration proposal, with professor Wang Qi Heng and Professor Yang Chang Ming from the Departtment of Architecture in Tianjin University to provide an initial master plan proposal. Members of the restoration committee were resolved in retaining the essence of ancient architecture; restoring the Mahavira Hall, Hall of the Celestial Kings, Bell and Drum Tower, Dharma Hall etc; building of the other halls, the corridor of the mountain gate, half-moon pond, archways, pagodas etc, thereby allowing for a more complete Conglin moanstery architecture. On the 16th of November, the Building and Construction Authority of Singapore issued a public note, declaring some of the halls in the moanstery as dangerous buildings. They were thus cordoned off and public access was removed in order for integration works to commence.